For many extreme applications, the benefits of using carbon fiber outweigh the costs, but surprisingly often professional engineers and part designers end up selecting another material for their parts.

“Why?” As it turns out, carbon fiber is so strong and so lightweight that it often exceeds the required specifications of the application which makes the additional expense unnecessary.

For example, a hobbyist designing a drone frame might consider carbon fiber to minimize the weight of their remote-control aircraft, or to ensure it is as resistant to breaking in a crash.

Or a product engineer might consider carbon fiber to enhance the marketability of a product.

So what do amateurs and professionals who choose a more economical alternative end up doing?

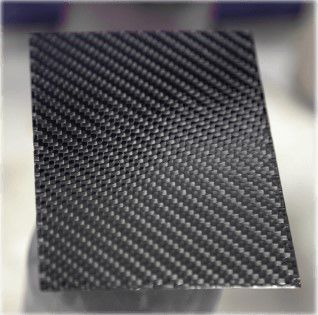

FR4 laminated fiberglass is very similar to carbon fiber. Both are composite materials, and both use a polymer resin to strengthen and thicken their substrate material. FR4 is almost as strong, rigid, light and resistant to thermal expansion.

As pricing is highly dependent on many factors, including design and quantity ordered, it is difficult to give an exact price comparison. However, generally speaking, FR4 laminated fiberglass parts are usually about half the cost.

What does all of this mean for you?

If cost is not a consideration and you want the lightest, strongest material possible, carbon fiber may be your best bet. If cost is a concern, laminated fiberglass has great potential.

As a non-scientific test, I decided to test some sample FR4 laminated fiberglass parts that we had lying around to see what kind of abuse they could take. The results were really impressive.

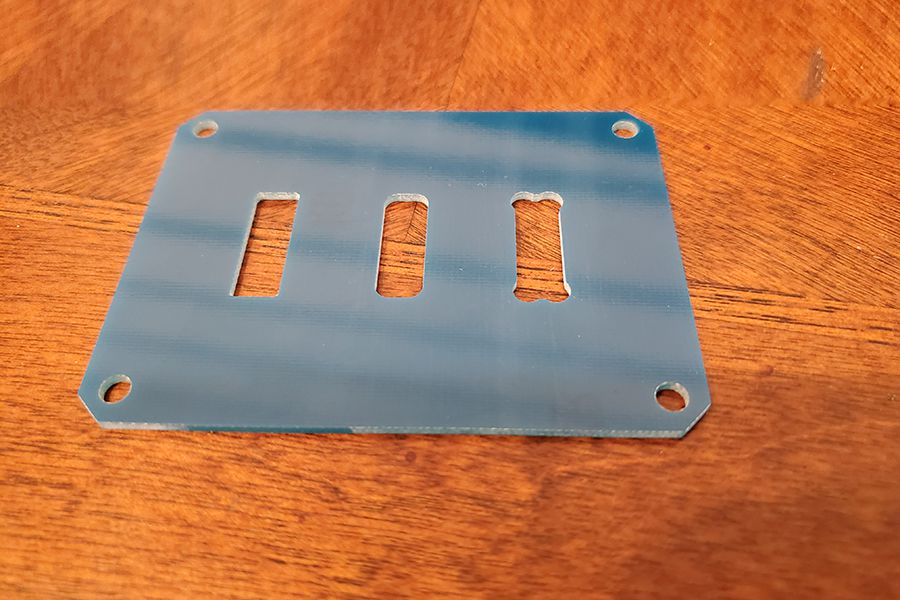

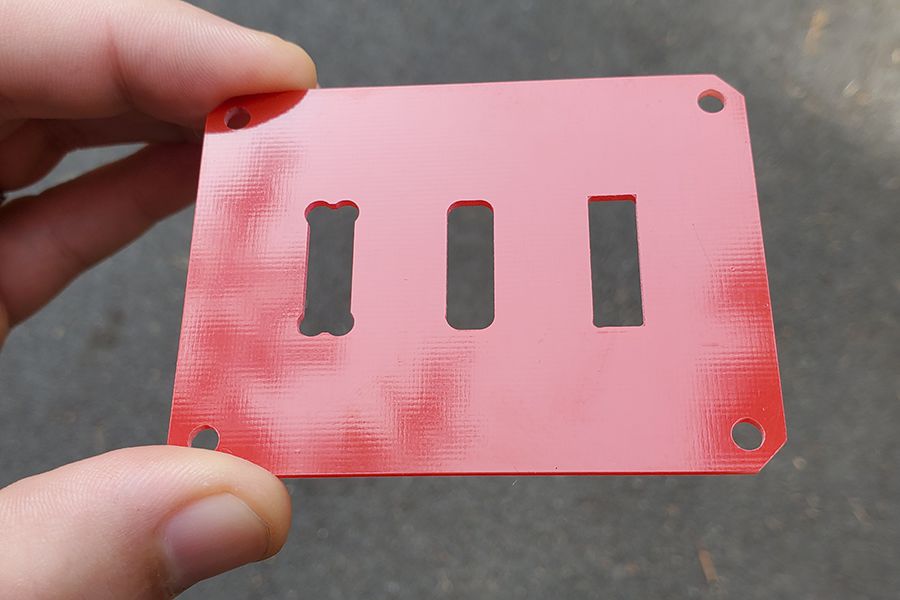

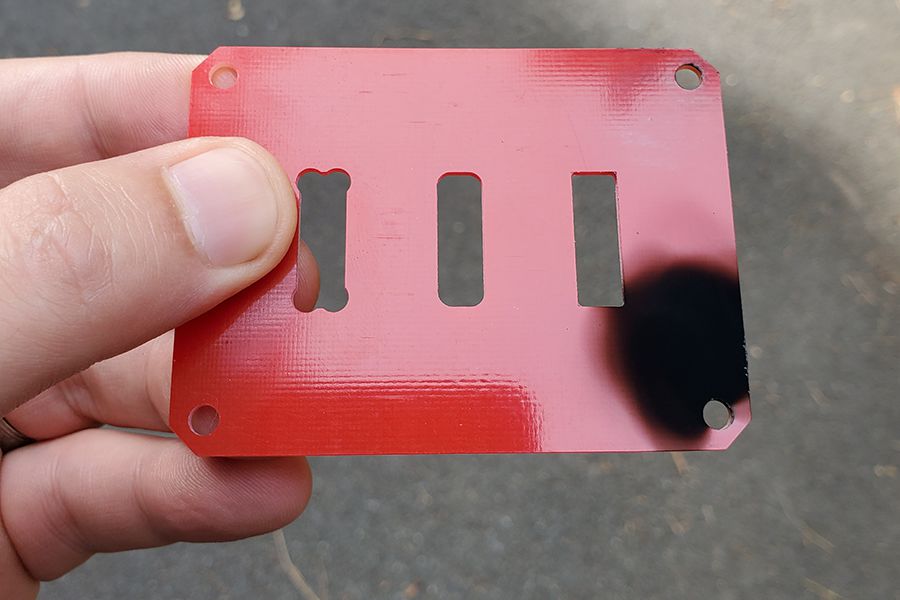

Each part was approximately 2” x 3” and 1/16” thick, with four mounting point cutouts and another 3 of varying shapes in the center.

At first glance, they don’t look all that strong, and they are definitely lightweight at under 0.4oz each, but once you try to break one, the benefits of laminated fiberglass become apparent quickly.

No matter how hard I tried I could not break one with bare hands. In fact, there was barely any flexing at all, and the parts did not appear to exhibit any signs of plastic deformation. Like carbon fiber, the strength of laminated fiberglass is due to the resin enclosed woven substrate material, and if you look closely at the surface of the laminated fiberglass material you can actually see the pattern or weave of the fiberglass.

Proceeding with my test I also left a piece in a glass of water for an hour to see what would happen as it is known that fiberglass can absorb moisture. Still, the part appeared unchanged and could not be broken by hand. I then placed the sample piece back into the glass of water for a full 24 hours. Same result.

I also decided to test if the parts were brittle and how they stood up to being flung against an asphalt driveway. Three times the part was flung into the driveway as hard as possible. Only minimal cosmetic damage resulted.

I then decided a scratch test was in order. Although when held flat against the asphalt the damage from this test seemed minimal, when scraping an edge the fiberglass did wear away.

I decided to up the ante and run one over with a car. But the parts appeared all but unscathed.

Running out of ideas I decided it was time to see how the part did when exposed to an open flame. With the material rated to 250+ °F the expectation was that it would quickly catch on fire, but instead it did not. For the first fire test I held the part approximately one inch above a standard handheld lighter for 15 seconds. A black circle developed and the part did begin to smoke a bit, but after the test the soot could be easily wiped off and the part appeared uncompromised. I then performed the same test for 30 seconds. Again, the part smoked a little, but the resulting soot was easily wiped off and the part did not appear very much impacted beyond a small amount of melting on the edge.

Then I decided to take off the gloves and expose the parts to serious destructive force in the form of a hammer. Placing the piece on an asphalt surface I let it rip. The first few strikes left barely any damage, and I wasn’t holding back. So I decided to give it 12 total strikes. After this the parts were visibly damaged, but still in one piece. At this point, I applied pressure to the fiberglass part by hand, and after a significant amount of force, it did eventually break in half.

Conclusion? First, that this test was not very scientific. But also that laminated fiberglass parts are extremely resilient to a smattering of significant and sustained destructive forces.

Laminated fiberglass has its own unique pros and cons, but it certainly does a great job of providing most of the benefits of carbon fiber at a fraction of the cost. After doing all of this testing it is a bit of a mystery why this material is not more commonly used when making parts.

Whatever material you choose, be sure to research its attributes compared to other materials and in relation to your needs. We all like to over-engineer, but no one likes to overspend.

Submit a CAD file to get a quote for your design, or design your part from scratch using eMachineShop CAD.